2016-12-05

You should not have any special fondness for a particular weapon, or anything else, for that matter. Too much is the same as not enough. Without imitating anyone else, you should have as much weaponry as suits you.

— Miyamoto Musashi, The Book of Five Rings

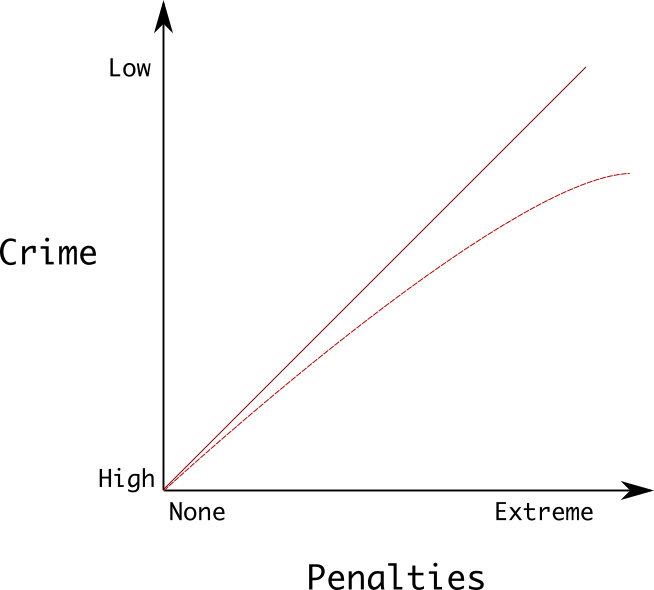

Linear relationships between things are easy to understand. More of this, leads to more of that. The more severe the penalties for crime are, the less crime there is. Simple non-linear relationships, like diminishing returns, are not much of a stretch further - more of this, leads to more of that at the start, but eventually plateaus out. At the extreme end of penalties for crime, it no longer lowers crime, since crime is presumably as low as it can it can realistically be.

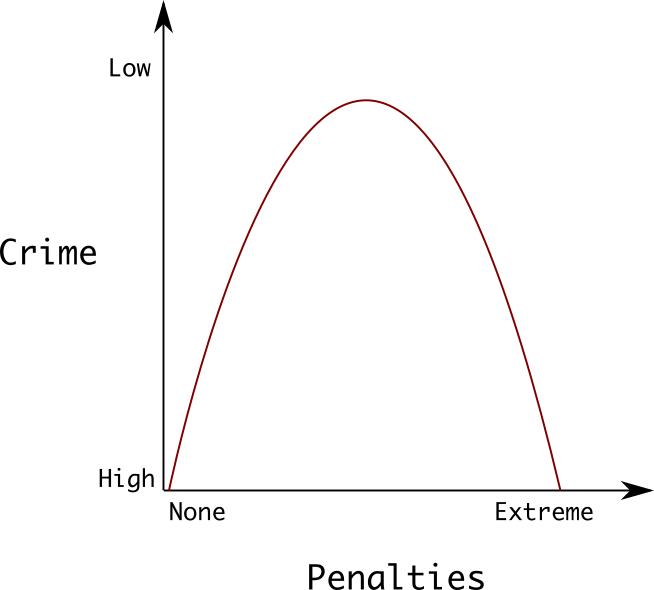

The problem is that in many real world relationships between things, there is a point of too much, where things not only plateau, but actively get worse - once a certain threshold is passed. And this is exactly what we tend to struggle with. You might think that one of the above relationships between crime and penalties make perfect sense; that it agrees with your intuition. But you'd actually be dead wrong.

Enter the inverted U shaped curve, introduced by author Malcolm Gladwell, in his book David and Goliath: Underdogs, Misfits and the Art of Battling Giants. Research, according to him shows that the real relationship between crime and the severity of penalties imposed looks more like this:

So crime actually starts getting worse again beyond a certain point. Why? He gives a synergy of reasons:

Despite obtaining their money illegally, criminals are bread winners too, and putting them in jail means their dependents suffer.

Children of a jailed parent are 3 times more likely go to jail themselves, and are two times likely to be depressed.

A stable marriage is one of the best predictors of children in disadvantaged communities living productive lives. Lengthy jail time tends to destroy marriages.

Freshly released prisoners tend to be worse off after being in prison, and struggle to readjust back into normal community life, often turning back to crime.

Gladwell gives us the threshold point for communities; if more than two percent of a community are jailed, we tend to see crime start getting worse again.

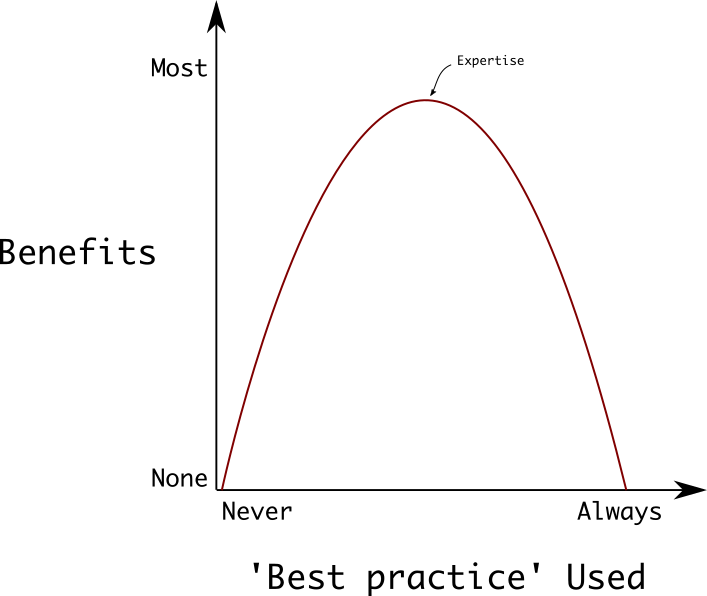

In software development, we tend to see the same patterns. The simpler relationships between things dominate our thinking, and our reasoning. We like to follow best practices, often without thought, under the mistaken assumption that more usually leads to better, or at worst, that it couldn't hurt. But what if the relationship between benefits and 'best practice' usage actually looked more like this:

Should code always be DRY? Should functions always be short? The more correct answer is - it depends. In the words of Won Chun, "Be skeptical of blind dogma. Expertise is nuanced." Expertise is finding the point on that curve where you derive enough of the benefits from following that 'best practice' to make it worth your while.

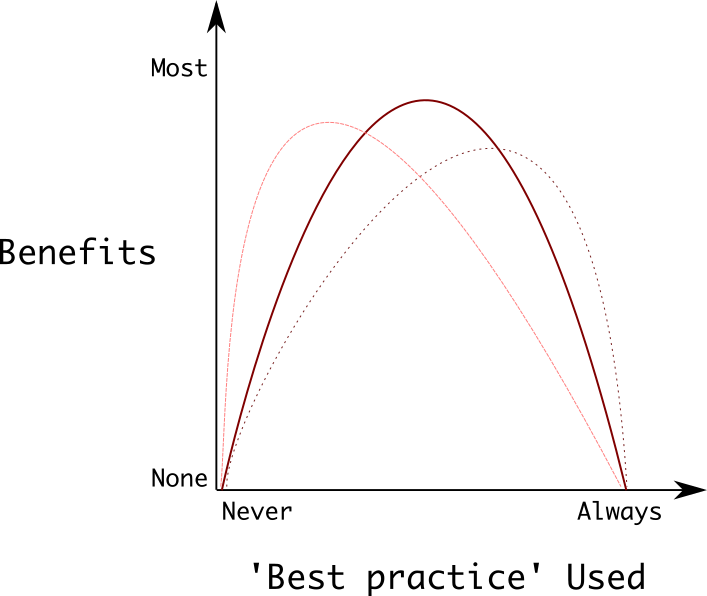

The point of just enough is always dependent on the best practice itself, and the context where you apply it. More than likely you have a set of curves, depending on your problem. For some, you might find that you get most of the benefits from a little bit of use, for others, you might need to use it almost always.

Programming will always be a holistic pursuit, with many intertwining factors. Linear models of the world are nice, but they can also act as horse blinkers - blinding us from reality.